On the use of epigraphs and metanarratives in Robin Hobb's "Assassin's Apprentice"

How Robin Hobb manipulates the conventional epigraph to create a narrative that will have me tearing through her fifteen book series in one year (probably)

My actual first attempt at talking about Assassin’s Apprentice

Have you ever?

Hm.

So sometimes I.

Erm.

I’ve gotta say

And now for a more articulate series of thoughts on the book.

Just a few months ago, I read my first Robin Hobb book, Ship of Magic. I found the reading experience of the book to be fine. That is, until I got to the last half of the book. Then everything started to click in my brain. The storylines began to wrap up, the book's conclusions hitting tremendously hard. Plots had well defined endings, while others left us wondering where the rest of the series would take them. Characters felt like they had undergone growth and change, while still feeling like there was more of their story to tell and more for them to learn. It was not until the end did I realize the deftness Hobb had to craft her story in just the right way to get the payoff from the end of this book.

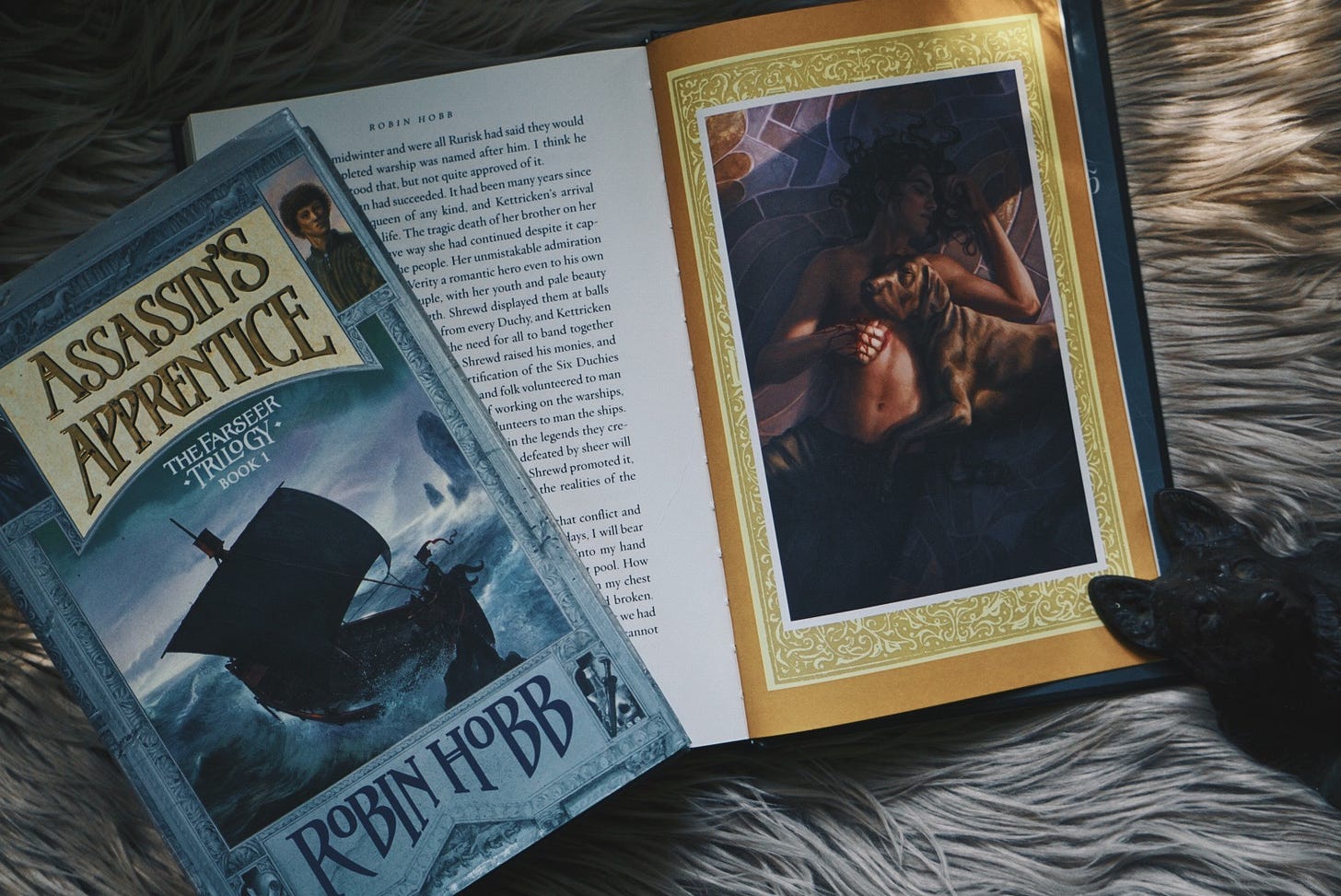

So, when I decided to pick up arguably Hobb’s most well known Farseer trilogy. I had big expectations.

And boy did she deliver.

I read the first book in the series, Assassin’s Apprentice, in just under a month. Given the book was shorter than most epic fantasy, I was happy with the progress I made. But by the end of it, I could smell Hobb’s touch all over the story, just as it covered Ship of Magic. I was so hooked that I immediately bought the second book in the series, Royal Assassin, and started to read it. I have never read a series of books in complete succession like that. But I couldn’t help myself.

My voracity was rewarded, because the second book had the notable Robin Hobb hard hitting conclusions that made my jaw drop to the floor. I am left dumbfounded as to how Hobb has so consistently made me feel such intense emotions with only the words on a page. But such is the beauty of reading, words alone are able to feel the widest range of emotions.

What I find special about Hobb’s storytelling in the Farseer trilogy, which is also what I want to talk about today, is the different tools in which Hobb tells the story. When I read and write, I am constantly fascinated how writers can flip writing mechanics and different narrative tools on their head. The simple conventions that we may take for granted in most novels can be manipulated in various ways to have very poignant effects. I think Hobb has cracked the storytelling code in this trilogy for several reasons, but I want to talk about one very specific way that Hobb uses to make her characters, world building, and narrative style so impactful, while also being one of the easiest facets of the novel for readers to overlook: her epigraphs.

In literature, an epigraph is a phrase, quote, or poem placed at the beginning of a story, chapter, or some other body of work. Typically, it is somehow related to the text that proceeds it contextually or thematically. You might be familiar with some other famous epigraphs. At the beginning of To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee includes a quote from Charles Lamb: “Lawyers, I suppose, were children once.” Mary Shelley includes a quote from Paradise Lost in a personal favorite of mine, Frankenstein: “Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay to mould me Man, did I solicit thee from darkness to promote me?” And Ray Bradberry includes a quote from Juan Ramón Jiménez before his sci-fi classic, Fahrenheit 451: “If they give you ruled paper, write the other way.”

Getting more specific into the realm of Science Fiction and Fantasy (SFF), epigraphs are one of several tools to aid a writer in telling their story. Some follow the traditional route of placing a quote that thematically encapsulates the novel the reader is about to read. But sometimes writers take the convention of the epigraph to further contextualize the fictional world they build within their story. The best examples come from SFF colossal, Brand Sanderson, who uses them frequently in his successful Mistborn and Stormlight Archive series. The epigraphs range from journal entries to death rattles, but ultimately they prove to somehow enhance or contextualize everything else the reader knows so far about the story they are reading.

Robin Hobb masterfully applies the epigraph in the Farseer trilogy, specifically in Assassin’s Apprentice. Not only does she utilize them to contextualize the setting and characters, but she even folds in other information to establish and enhance the metanarrative framework of the series.

Before I dive into metanarratives, I should probably explain how I am using the term here. When I say metanarrative, I am talking about how the means in which the story is delivered to us tells a story in and of itself, one that is separate to the one that novel is focused on. In the case of the Farseer trilogy, the story is told from the perspective of the series’ main protagonist, Fitz. He delivers it from the first person present, as Fitz documents an account of the history of the Six Duchies (the setting of the story). It reads as if we are reading from the same tome he actually scribed upon. So, it is established in the first chapter of the story that we, the readers, are reading a first hand account of the history of the Six Duchies as documented by Fitz himself.

Except it isn't that simple.

The first epigraph of the story reads exactly like how a textbook of a real world country might start:

A history of the Six Duchies is of necessity, a history of its ruling family, the Farseers. A complete telling would reach back beyond the founding of the First Duchy and, if the names were remembered, would tell us of Outislanders raiding from the sea, visiting as pirates a shore more temperate and gentler than the icy beaches of the Out Islands. But we do not know the names of these earliest forebears.

And of the first real King, little more than his name and some extravagant legends remain…

A pretty informative, yet boring, introduction epigraph. However, the first paragraph of the series that follows it is what enhances the epigraph. In conjunction, the two establish the narrative framework for the novel and consequent ones in the series. It's a longer one, so I will share it below, then give a more in depth summary of how perfect this sets up the rest of the series.

My pen falters, then falls from my knuckly grip, leaving a worm’s trail of ink across Fedwren’s paper. I have spoiled another leaf of the fine stuff, in what I suspect is a futile endeavor. I wonder if I can write this history, or if on every page there will be some sneaking show of bitterness I thought long dead. I think myself cured of all spite, but when I touch pen to paper, the hurt of a boy bleeds out with sea-spawned ink, until I suspect each carefully formed black letter scabs over some ancient scarlett wound.

Both Fedwren and Patience were so filled with enthusiasm whenever a written account of the history of the Six Duchies was discussed that I persuaded myself the writing of it was a worthwhile effort. I convinced myself that the exercise would turn my thoughts aside from my pain and help the time to pass. But each historical event I consider only awakens my own personal shades of loneliness and loss. I fear I will have to set this work aside entirely, or else give in to reconsidering all that has shaped what I have become. And so I begin again, and again, but always fine that I am writing of my own beginnings rather than the beginnings of this land. I do not even know to whom I try to explain myself. My life has been a web of secrets, secrets that even now are unsafe to share. Shall I set them all down on fine paper, only to create from them flame and ash? Perhaps.

There is SO much to break down in these two paragraphs, so lets start:

The first paragraph so perfectly encapsulates what we are going to be reading from here on out. We learn that Fitz, in the present, is writing something. His knuckly grip (which might clue us in to that he is old) falters, soiling someone named Fedwren’s paper. “Oh,” might think the reader, “The epigraph we just read was penned by Fitz!” Yes, indeed it was. This claim is confirmed in the following two sentences. Fitz writes that he is attempting to write a history. What history? The history we just read in the epigraph. A history of the Six Duchies.

But what is this tonal shift? Why is Fitz writing about himself instead of focusing fully on the facts? Well, he has doubts, and explains as such, since every time he attempts to write, bitterness he thought dealt with resurfaces, bringing him back to pain he experienced as a child.

This begs the series’ paramount question: “What happened to Fitz?”

In the second paragraph, we are given even more details to support the narrative framework set up in the previous one. We learn that Fitz had to persuade himself to write a history because of the excitement it evoked in Fedwren and someone named Patience. Who are these characters? They like history? They must be bookish types. Who are they relative to Fitz? These are a few basic questions prompted by name dropping unknown characters like this.

But, of course, it isn’t that simple. The issue seems more personal. Fitz admits that this writing was also hoped to be a distraction. A distraction from pain. What pain? Each historical event he recounts is difficult for him. Why? Because he will inevitably have to set this project aside or reconsider “all that has shaped what I have become.” Woah, that’s a lot to sit with. Fitz must be at odds with a TON of the history of the Six Duchies. Not only that, he is actually worried that documenting this history might force him to view himself differently in the light of the grander development of the Duchies, which could, we assume, make him look like a bad guy.

This is the core issue with Fitz attempting to write this history. He is human and has emotions. His story is fully fleshed out and heavily intertwined with the machinations of the Six Duchies. And rather than try to give a factual retelling of the Duchies’ history, he inevitably slips into his own story, speaking from the tone he writes presently. Even if he wanted to be completely factual, he cannot help but speak about his own story. Be it not of pride, but of loneliness, loss, and sorrow.

Again: WHAT HAPPENED TO FITZ?

We then shift our mind back to the topic of metanarratives. While the bulk of this book’s main narrative is Fitz's life, the metanarrative is Fitz in the present day as he writes. Every detail, epigraph, and whatever else that clues us in to Fitz’s present day circumstances is the metanarrative. While we slowly learn about Fitz’s life, we learn things like the fact that Fitz is far older as he tells the story and is in pain, so much so that he convinces himself that writing this history could distract him from it. This isn’t a ton of detail, but it is enough to get us curious and interested in the story that Fitz has to tell. We want to know what happened to Fitz and how he got to where he is now, wherever and whenever that might be.

With the reader’s curiosity brimming with questions about present day Fitz, as well as his younger self, Fitz continues to tell his personal story, as opposed to readopting the factual, textbook entry about the Six Duchies. But before continuing on that path, the second chapter starts with an epigraph about the first king of the Six Duchies, Taker. After the epigraph, Fitz slips back into telling his own personal story.

Thus, a pattern is established. Take note of this. The epigraphs at the beginning of each chapter will have historical facts about the history of the Six Duchies, like its kings, landmarks, and culture, followed by the main focus of the chapter, Fitz’s personal story. And we get our fill. For the next five chapters, we get seven informational epigraphs about the Six Duchies followed by Fitz’s personal story. In doing so, we can imagine that Fitz is trying to uphold some separation between his own story and the true history of the Six Duchies. But then, we find an anomaly that changes this pattern in the epigraph for Chapter 7.

There were rumors of poison when Queen Desire died. I chose to put in writing here what I absolutely know as truth. Queen Desire did die of poisoning, but it had been self-administered, over a long period of time, and was none of her king’s doing. Often he had tried to dissuade her from using intoxicants as freely as she did. Physicians had been consulted, as well as herbalists, but no sooner had he persuaded her to desist from one than she discovered another to try.

Toward the end of the last summer of her life, she became even more reckless, using several kinds simultaneously and no longer making any attempt to conceal her habits. Her behaviors were a great trial for Shrewd, for when she was drunk with wine or incensed with smoke, she would make wild accusations and inflammatory statements with no heed at all as to who was present or what the occasion was. One would have thought her excesses toward the end of her life would have disillusioned her followers. To the contrary, they declared either that Shrewd had driven her to self-destruction or poisoned her himself. But I can say with complete knowledge that her death was not of the King’s doing.

Whenever we as readers and scholars see a break in an established pattern, there is almost always a reason for it. And with a writer like Robin Hobb, you can guarantee there is significance to it. While at first glance this seems to be a recounting of the death of Queen Desire, there is a lot of bias and malice laced in Fitz’s “history” of Queen Desire’s death. This should immediately alert us to the potential of an unreliable narrator. We should probably be wary of this, given that we already know these epigraphs are written by Fitz himself. Just look at the second sentence of the epigraph, “I chose to put in writing here what I absolutely know as truth.” Hobb is practically smacking us over the head to be wary of what we accept as truth. Although we have come to know Fitz as a standup guy through hearing his story, by no means is he a man who wouldn’t lie to accomplish his goals. Even if this were not the case, we can deduce that Fitz has a very negative disposition towards Queen Desire through his describing her as reckless, inflammatory, and a careless drunkard.

This break in the pattern causes a shift in our outlook on the epigraphs we’ve been presented with up until now. Now that Fitz is starting to lose the ability to keep his own opinion out of the true history, we pluck some small details or speculate things about Fitz's story. For example, one might ask why Fitz is so obstinate that he knows the true cause of Queen Desire’s death. The last sentence gives a hint, “...But I can say with complete knowledge that her death was not of the King’s doing.”

And so thickens the metanarrative! One might assume that Fitz might be writing this because there is speculation that the King did kill the Queen! Or maybe Fitz! Because by this time in the story, we know that Fitz has begun his training to be an assassin! If this is the case, then we know present Fitz might be in some hot water! He even said it himself in chapter 1, “My life has been a web of secrets, secrets that even now are unsafe to share.”

This is just one example of how epigraphs are leveraged in Assassin’s Apprentice. Hobb’s metanarrative that she leverages through the use of epigraphs creates a unique lens to reveal information about characters. Rather than waffling between present day and flashbacks, Hobb leaves it up to the reader to do some light investigative work to enhance the main narrative. It gives the reader a sense of accomplishment, propelling them to read further. Add in the slow congealing of fact and fiction in the epigraphs also thematically lines up with the obstacles in Fitz’s life perfectly. In Fitz's story, he is often faced where parts of his identity clash or where his allegiance to one person conflicts with another. In this way, Fitz is torn in several different ways, even by those he trusts the most, in order to live a life he wants to live.

As the chapters go on, Fitz continues to mix his personal history with the Six Duchies’ history in the epigraphs. The history becomes more contemporary to the time surrounding Fitz’s retelling of his life, to more relevant events and groups of people. This is where Hobb uses epigraphs to enhance Fitz’s story rather than vice versa. She does so through recording biographical info about the characters Fitz at his life at Buckkeep. In chapter nine’s epigraph, Fitz gives a history of The Fool, though more is speculated than known. In chapter thirteen’s epigraph, Fitz talks about Lady Patience, the wife of Fitz’s father and step-mother to Fitz. In chapter fourteen’s epigraph, Fitz talks about Galen, the Skill master at Buckkeep and main antagonist of Assassin's Apprentice. All these epigraphs raise very important details about the characters in ways that are NOT disclosed anywhere else in the book. In sharing info this way, Hobb continues to blur the line between Six Duchies’ history and Fitz’s history. There is even some blatant foreshadowing to details about some of the characters that I can’t believe I missed until rereading these to write this essay. Not only is Hobb upturning the conventional use of epigraphs in novels, but she is also upturning her own epigraph conventions that she has already established!

While many of the epigraphs couple with particular details of the book masterfully, I don’t want this essay to stray too far from the topic of epigraphs and metanarratives. We will move to the last epigraph of Assassin’s Apprentice, which serves as the book’s epilogue. I don’t know if you have ever exclaimed aloud while reading a book, but I kid you not, I did upon finishing just about every sentence in this epigraph.

“You are wearied,” my boys says. He is standing at my elbow and I do not know how long he has been there. He reaches forward slowly, to lift the pen from my lax grip. Wearily I regard the faltering trail of ink it has tracked down my page. I have seen that shape before, I think, but it was not ink then. A trickle of drying blood on the deck of a Red-Ship, and mine the hand that spilled it? Or was it a tendril of smoke rising black against a blue sky as I rode too late to warn a village of a Red-Ship raid? Or poison swirling and unfurling yellowishly in a simple glass of water, poison I had handed someone, smiling all the while? The artless curl of a strand of a woman’s hair left on my pillow? Or the trail a man’s heels left in the sand as we dragged the bodies from the smoldering tower at Sealbay? The track of a tear down a mother’s cheek as she clutched her Forged infant to her despite his angry cries? Like Red-Ships, the memories come without warning, without mercy. “You should rest,” The boy says again, and I realize I am sitting, staring at a line of ink on a page. It makes no sense. Here is another sheet spoiled, another effort to set aside.

“Put them away,” I tell him, and do not object as he gathers all the sheets and stacks them haphazardly together. Herbary and history, maps and musings, all a hodgepodge in his hands as they are in my mind. I can no longer recall what it was I set out to do. The pain is back, and it would be so easy to quiet it. But that way lies madness, as has been proven so many times before me. So instead I send the boy to find two leaves of carryme, and ginger root and peppermint to make a tea for me. I wonder if one day I will ask him to fetch three leaves of that Chyurdan herb.

Somewhere, a friend says softly, “No.”

The beauty of the metanarrative crafted in this series is for the reader to try and connect the dots from the Fitz we follow in the story and the Fitz who tells the story. For example, someone who Fitz refers to as “my boy” tells the older Fitz to call it quits for the evening, to stop writing. What’d Fitz call him? “My boy?” Fitz has a son? With who? And when? The Fitz in the story is only in his teens at this point! And he has so many other issues that we can’t even begin to speculate any romance! So then what happens to Fitz between then and now?

More details than Fitz’s parenthood are revealed too through Fitz's associations of the image of ink tracking down the page. By comparing it to drying blood on the deck of a Red-Ship, we can assume Fitz at some point will board andfight on a Red-Ship. Or that Fitz continues down the path of an assassin by dolling out poisons, almost begrudgingly. More than that, Fitz cannot even remember what he set out to do with his writing. In saying as much, we can assume there lies little to no separation from a true history of the Six Duchies and Fitz’s personal story.

(The last sentence of the first paragraph even gives us a nice call back to the first chapter with, “Here is another sheet spoiled”.)

Fitz once again mentions a persisting pain. Given that we are not aware of any incident so far, we must also speculate that something drastic will happen to him such that he experiences it chronically. (Can you imagine why I might like this character?)

On a more grim note, Fitz makes a callback to Chapter 21’s epigraph by mentioning carryme:

Of the Chyurdan herb carryme, their saying is, “A leaf to sleep, two to dull pain, three for a merciful grave”

The implications of Fitz musing on whether he will ever ask for three leaves are difficult to swallow, but makes sense, given that Fitz confronts the idea of suicide several times in Assassin’s Apprentice. However, we are instantly warmed by the last, lone sentence of the novel.

While this is not only a very touching moment, it also reveals a very important piece of information about Fitz’s story going forward. We can only assume that the friend Fitz is speaking with is a beast of some kind, communicating with Fitz via the Wit. The Wit is a magical means of bonding with animals, allowing for the two to share thoughts, senses, and communicate over a distance. While seemingly harmless, the Wit is frowned upon in the Six Duchies, where the punishment for practicing the Wit could be death (by drowning, more specifically). While it is only a semi-major point of conflict in Assassin’s Apprentice, Fitz using the Wit is a much more substantial conflict in the next book in the series, Royal Assassin. It remains to be seen whether the same could be said about the third book, Assassin’s Quest, but I’m almost certain it will be. Nonetheless, the sentence confirms this: Fitz continues to practice the Wit. And he will until he is an older man. So, no matter how much Fitz may struggle to not use it, we know that he will in the end.

Now, can any and all of what I have shared today change by the time I read the next book? Absolutely. But this will only further cement this series as one of the greatest of all time. So much can be said now about how information is revealed in the second book just as I have for the first. Maybe I’ll just have to write an entirely new essay on Royal Assassin. And maybe for Assassin’s Quest, too. I just have to get the last book. My birthday is this month. Brothers of mine, if you are reading and want an easy birthday gift, get me Assassin’s Quest by Robin Hobb. Or you can, listener. Then I can say I have started to profit from my work 😛

Why any of this matters

Becoming a fiction writer has been a very strange path to walk. Never in my life have I needed to be so in touch with my creative side. And in a sea of other work to compare my own against, it can be daunting to start at all. I mean, when you have an endless supply of “classics” (regardless of genre), why would you ever waste your time on some author of no renown’s work? Such are the thoughts that hinder my foray into the creative world. However, when I finish reading a work Hobb’s, I am so incredibly invigorated and moved to create something of my own. Many writers may often ask who your influences are, or who you would liken your writing style to. One day, I’d love to say I come even remotely close to Hobb’s style.

Assassin’s Apprentice and her other works I’ve read have consistently moved me emotionally. Right now, I have cried at least once reading three of the three books I’ve read of her’s. Am I crying over solely her ability to use an epigraph? No. But I write and adore her application of them because of its ability to enhance the story she is trying to tell. It would be much easier for her to write Fitz’s story from beginning to end and ignore the narrative hoops she had to jump through for her to pull off the metanarrative in Assassin’s Apprentice. And it would still be a good story too. But, we would lose certain nuances that make Hobb’s books such a joy to read.

Her use of epigraphs gives us a more robust understanding of the world her characters occupy. For Fitz, we learn about his story by her unveiling details about Fitz the child and Fitz the old writer. Other characters are nudged slightly in specific directions to help the reader understand them on a deeper level. By giving some of these details to the reader, she helps them to foresee where Fitz’s story might be headed, giving us a huge sense of accomplishment in correctly judging a character or unraveling the motivation behind a character’s actions. I was blind to it the first time I read through the book, but going back and rereading the epigraphs revealed an immense amount of strategically placed, yet subtle, foreshadowing to events that occur later in the book, or even the second. And if not foreshadowing plot events, she might even tell a story that parallels another event thematically, so we are subconsciously expecting a character’s actions, but not necessarily surprised. Hobb masterfully rewards the attentive reader, but goes as far as to prime the unattentive one to enjoy the story just as much as someone who might write a whole essay about it.

If you have read Assassin’s Apprentice, I’d love to hear your thoughts. I will be sure to update you all when I read the third book and how that goes. Let me know what you think of the whole idea of metanarratives and epigraphs in the comments so I can engage with you.

A goodbye

Until next time!